The Boy Travelers - Japan and China

The Boy Travelers

The Boy Travelers - Japan and China

The Boy Travelers

The Boy Travelers - Japan and China

The Boy Travelers

The Boy Travelers - Japan and China

The Boy Travelers

Study the chapter for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

Activity 2: Study the Chapter Pictures

Activity 3: Observe the Modern Equivalent

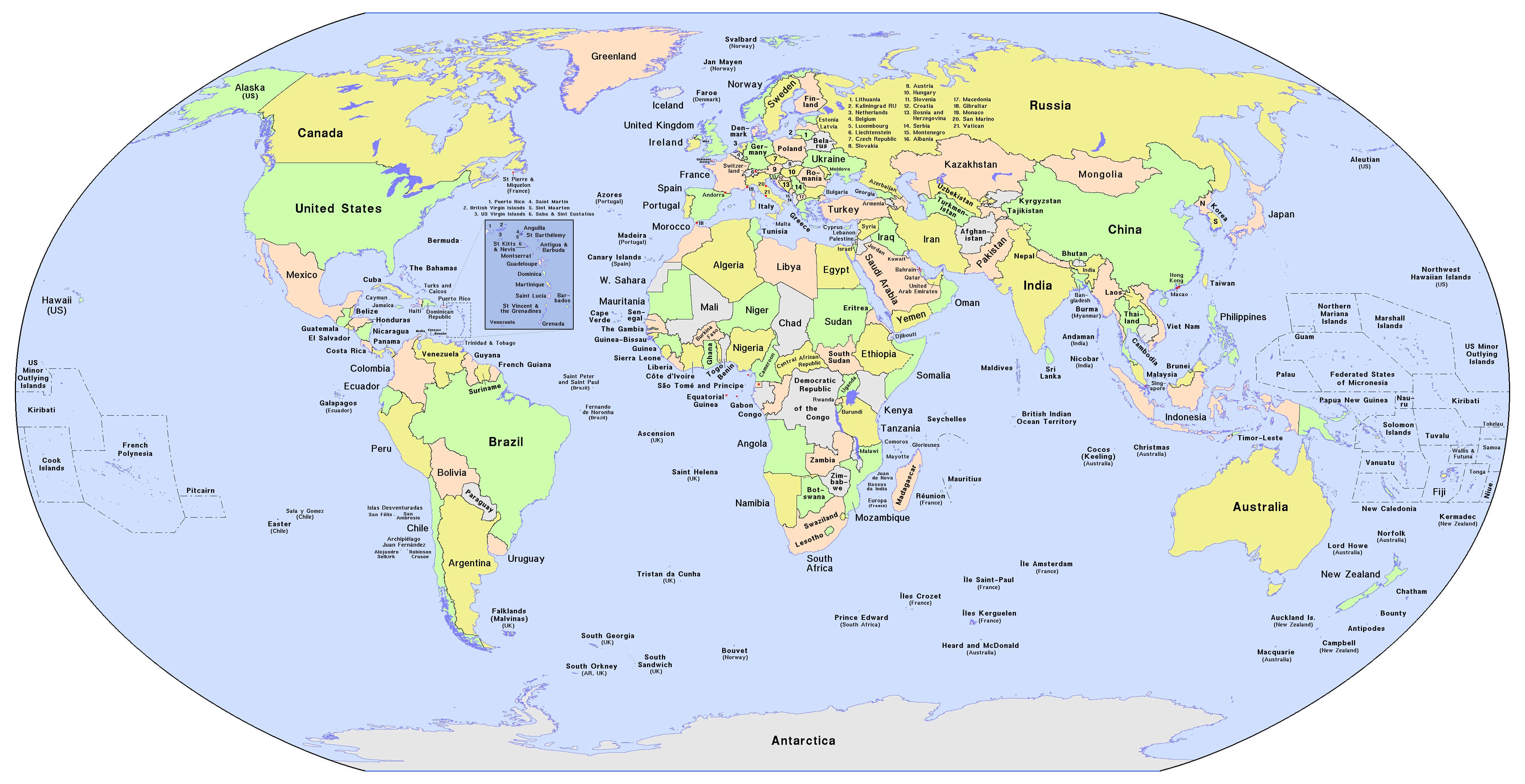

Activity 4: Map the Chapter

Activity 5: Map the Chapter on a Globe